Blue Light: The Sleep Thief

March 8, 2023

It was 3 am, as I laid in bed feeling like I had just drank a large coffee. I was wired, with sleep no where in sight and a bottle of melatonin gummies at my bedside that I didn’t want to become reliant on. My aid in winding down, my phone, was really my nemesis as its blue light emissions tricked my brain into keeping me awake.

We live in a world where phones, tablets and computers are constantly used, and blue light emissions engulf us. This artificial light affects all users of technology, especially prior to bedtime. Could blue light be the reason our population is becoming restless?

The human body is like a clock, with the retina in our eye being the control center. As bright light hits the retina, a signal is sent to the brain to suppress melatonin, the chemical that initiates that sleepy feeling. However as more researchers have studied the effects of blue light, they found that this wavelength suppresses melatonin more than any other form, which leaves electronic users especially wired prior to bedtime.

A little extra blue light never hurt anybody, however the issue stems from the fact that electronic users are scrolling later and later into the night, while screens continue to become brighter. The National Sleep Organization decided to take a deep dive into this issue in 2014. They found that, “…89 percent of adults and 75 percent of children in the U.S. have at least one device in their bedroom, with a significant number of them sending or answering texts after they had initially fallen asleep,” (Jabr).

George Brainard, neurologist at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia was one of the first people to study how light can effect the circadian rhythms and hormones of the human body. He conducted studies to see how the brain directly reacted to light sources, especially those that produced blue light, and the levels of melatonin that were produced after this exposure. “Light works as if it’s a drug, except it’s not a drug at all,” Brainard says.

The results of this experiment were extremely conclusive. When comparing melatonin levels after men looked at a dim computer screen before bed versus a fluorescent computer screen, the levels of melatonin produced were vastly different. The fluorescent screen resulted in minimal melatonin levels, and this hormone deficit persisted throughout the night. This test really just expresses how large of an effect blue light has on the human brain (In The Eyes..).

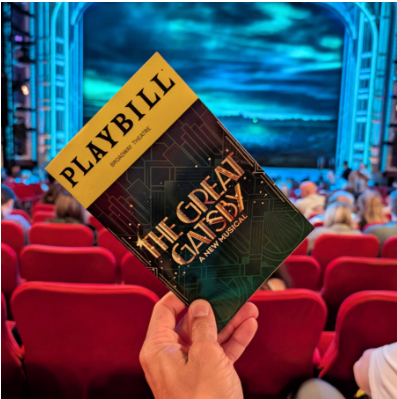

So what can be done to help us achieve that deep rem cycle at night? There are many easy things technology users can do, such as switching screens into a night mode that produces softer light waves and appears a more orange hue. Blue light glasses are also a remedy that have soared in popularity the last few years, but are very useful for blocking and filtering out blue light emissions.

Christian Cajochen, head of the Center of Chronobiology at the University of Basel in Switzerland has a different approach to helping regulate our sleep-deprived population’s nighttime schedules. While many scientists have looked into solutions like tinted glasses and light settings on your phone, Cajochen has considered completely altering the lighting within your household. According to his research these changes are very effective, especially when paired to just turning off the phone all together. “If people can figure out ways to simulate changes in sunlight across the day, that would be perfect,” Cajochen says.

However the most effective solution of all is electronic abstinence. Yes, that means close those computers, turn of TikTok, power down Netflix and catch some good old fashioned zzz’s. “Artificial light has been enormously beneficial over the centuries. But there are times, especially at the end of the day, when it can be too much of a good thing,” (Jabr).