Despite the whipping wind, setting sun, wet flurries, and incomplete homework, Thursday night was a glorious night for sledding. We made the journey to Pioneer Hills golf course. Being far from golfing season, the course was completely undisturbed; everywhere from the parking lot to the steep hills were blanketed in thick snow, primed for my SnowBoogie. As we trudged through the snow, though, I found that I wasn’t thinking about the sledding at all, but rather my phone that I had left in my car.

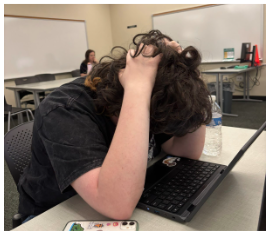

Regardless of valiant efforts with greyscales, timers, and impromptu app-deleting, I have always found myself back to my old ways of eight hour screen times. So I tried something new: physically distancing myself from that little homewrecking machine. I found that the less I was around it, reaching for it, and checking its screen, the less I felt connected to it and to its toxic effects on my life.

This little rectangle–that we call a phone–turns the best of us into a neck-scratching addict selling his childhood trophies to get a fix. The high of a phone is peculiarly like the high of a drug. As John Hopkins’ Jennifer Katzenstein explains, the reinforcement of dopamine pathways (from social media, text messages, etc.) makes us happy when we have it and experience withdrawal-like symptoms when we don’t.

This little rectangle turns the best of us into a woman nervously pacing as she awaits her lover who was supposed to be home hours ago. In their psychology journal exploring the impact of smartphones on cognition, Henry H. Wilmer, Lauren E. Sherman, and Jason M. Chein found that the simple presence of a phone reduces cognitive functions. Along with that, because we are all so used to constantly having our phones with us, we feel genuine anxiety when that presence is not there.

So despite the depression, anxiety, and erosion of relationships that Katzenstein, Wilmer, Sherman, Chein, and countless other professionals have found to be caused by excessive phone use, we stick with its toxic force because…it makes us feel good.

Not only are phones fun, but frustratingly practical. A cell phone is the multitool of all multitools: a calculator, computer, landline, dictionary, encyclopedia, and atlas all at once.

It’s unsurprising that many people have found themselves at this crossroads before, weighing the need for a practical life with a phone and a happy life without one. Many choose to compromise with their phones built-in wellness features like app timers and greyscales. Yet how do these few features hold up against the multitude of features intended to do the exact opposite and keep the user on the phone? Not well, it turns out. In fact, in the Washington Post article “Why setting time limits for TikTok or YouTube may backfire” Shira Ovide found that after setting time limits for the app, TikTok users ended up spending seven percent more time on the app than before.

So, how do we push away this toxic drug and lover that are our phones? Well, we do just that! We push our phones away. We leave them out of our rooms when we sleep. We turn them off when we are with our friends. It is crucial, integral, and unbelievably important that we protect the most important parts of our lives. Because it is the most precious, fragile parts of life–the sleep and the social interaction–that when taken by phones have the most dire consequences. My suggestion is not one of those convenient (yet ineffective) tools or settings, but a tangible opportunity for control over your own life.